Growing Up Apart

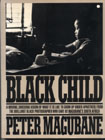

Review of Black Child by Peter Magubane. Alfred A. Knopf. 102 pages, $8.95 paperback.

Peter Magubane, in his years as a news photographer for Drum magazine and then the Rand Daily Mail, created many of the images that have made up the American conception of South Africa. With a home in Soweto, Magubane has seemingly managed to be on hand for every significant event in the history of resistance to apartheid. His first book, Magubane's South Africa, showed us the defendants in the Treason Trial being loaded into prison vans, black constables hurrying bodies away from the site of the Sharpeville massacre, and armored vehicles -- "hippos" -- deploying in order to block a student march. So potent were the images of political violence in that book that it was easy to miss some of the quieter scenes: a boy singing at the piano, a worried-looking baby being passed from hand to hand at a church celebration, and two Xhosa men on horseback, with pipes and peaked hats, coming home as the sun sets behind a hilly ridge in the Transkei.

In Black Child, the new book, the scenes of domestic life predominate far more. On the cover of the first book was a German shepherd police dog lunging at a black man; on the cover of the second is a small boy washing dishes in a dark kitchen. What Magubane gives us in Black Child is not as obviously polemical as before. There are many happy children in these pages, whether grouped around a birthday cake, playing soccer in the street or saying Ah for the nurse at the school clinic. Some of these photos seem cheerful enough for use in government propaganda -- especially one in which a grinning white schoolboy presents oranges and paraffin heaters to the appreciative students at a black grade school. The caption tells us that white schools often adopt black ones as a charitable cause.

The bad news comes later: the corrugated iron shacks, swollen bellies and urban rubble. But even this is more than a catalogue of the horrors of apartheid. Just as Magubane refused in his first book to gloss over such inconvenient and troubling matters as the violence by Zulu workers during the Soweto uprising, here too he gives us all sides of the story. We see the fervent protesters of 1976 with fists and placards, but we also see two young looters taking advantage of the beerhall demonstrations to make off with a couple of cases of Castle Stout. One group portrait of three Johannesburg street toughs is a study of insolent grace under pressure. The girl in the picture rolls her eyes towards her friends as if making some wry comment on the photographer who seems to find glue-sniffing such an interesting activity.

Magubane has written that at Sharpeville in 1960, where he arrived on the scene only minutes after the shooting stopped, his horror at the dead bodies prevented him from doing first-rate photography. From then on he decided that the pictures would always come first. "I no longer got shocked; I am a feelingless beast while taking photographs." The pictures in the first book reflected this philosophy. Many were deeply emotional, but they were detached as well, showing no hint of the photographer's presence as a person. In Black Child, seemingly a much more personal book, there are many more pictures whose subjects look directly at Magubane, conscious both of him and of themselves as figures in the camera's eye. There are also, for the first time, two pictures of Magubane himself in the midst of the events he chronicles. In one he is standing in the compound of a farm after bringing food and blankets for the workers. A heavy-set man with glasses, a forage cap and a camera slung around his neck, he seems awkwardly out of place. He has set aside his role as photographer to deal with an urgent human need, and he looks uncomfortable doing so. But in the other picture, marching with a crowd of children to the funeral of a student, he strides purposefully and does not look up.

Black Child, which begins on the frontispiece with a haunting picture of small children suspended in the smoky evening sky a few feet above a trampoline, ends with the backs of mourners as they walk away from the grave of Hector Peterson. The book becomes more somber as it goes along, moving from the detailed, sensitive scenes of birth, baptism, and town life, to poverty and starvation in the homelands and townships, then to various forms of child labor and finally to the hasty, sometimes blurred images of street violence. Last of all is an eerie stillness: the graveside scene with plastic-wrapped flowers left on the freshly-turned earth, and the white vestments of a minister who is walking away with a little knot of mourners.

Published in IDAF News Notes, June 1983.